Sunken Civilisations and Living Reefs: Parque de la Atlántida

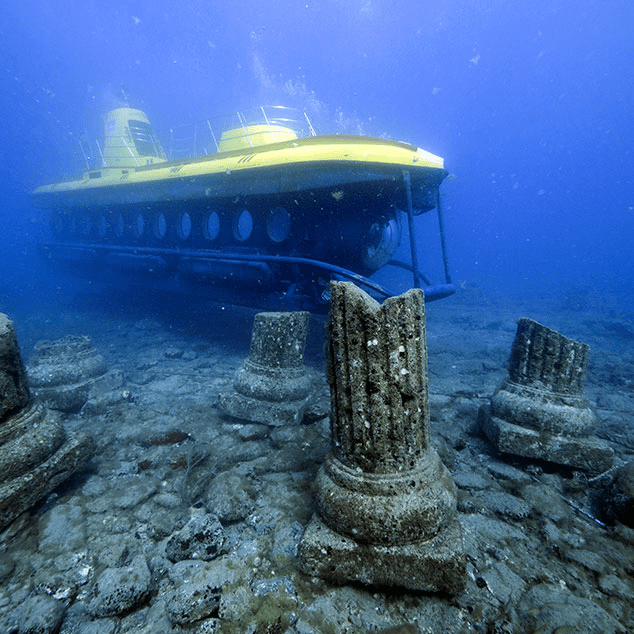

Sunken Civilisations and Living Reefs: Parque de la Atlántida https://pharosproject.eu/wp-content/uploads/2026/02/parque-submarino-la-atlantida-4-300x300-1.jpg 300 300 PHAROS Project PHAROS Project https://pharosproject.eu/wp-content/uploads/2026/02/parque-submarino-la-atlantida-4-300x300-1.jpgIt is a peculiar sensation, hovering thirty metres below the surface of the Atlantic, watching a school of barracuda drift through the stone columns of what appears to be a sunken temple. The light filters down in dusty shafts, illuminating structures that feel ancient, mythical. Yet, the concrete beneath my fingers was laid in 2017.

On the final day of January, the waters surrounding Gran Canaria and Lanzarote became less a tourist playground and more a living laboratory. The PHAROS project, an ambitious EU project aimed at restoring ocean health across the Atlantic and Arctic basins, threw open its hatches for a Citizen Science Marine BioBlitz. The mission was twofold: to engage the public in marine data collection, and to showcase a radical proposition, that we can build ecosystems back from scratch.

What the assembled divers and marine biologists encountered on the seabed here is not merely a series of pretty dive sites. It is potential evidence of a new methodology for marine conservation. Three of the four locations visited are artificial reefs, and they are being scrutinised as potential templates for large-scale restoration efforts from the fjords of Norway to the coasts of Portugal.

The crown jewel of this underwater showcase, and the site that holds particular emotional weight for the PHAROS team, is the Parque de la Atlántida.

Located just a short boat ride from the picturesque harbour of Puerto de Mogán, this underwater park is a curious marriage of art, tourism, and hard science. It was here, in the vessels of the Golden Shark submarine, that the PHAROS consortium held its inaugural meeting, peering through portholes at the very site that might prove their thesis correct.

The park is not a dumping ground of old tyres or scuttled ships. It is a deliberately designed seascape featuring over 350 individual structures crafted from pH-neutral concrete and high-density fibreglass. The aesthetic choices were deliberate; the modules are cast to resemble the ruined architecture of a lost civilisation, a deliberate nod to the Atlantis myth to capture the public imagination.

Yet beneath the romantic veneer, the ecology is brutally pragmatic. In less than a decade, these artificial ruins have ceased to be “artificial.” The bare concrete is now smothered in a Technicolor crust of algae, sponges, and coral. The open water spaces between the columns are thick with fish life. On the dive, we observed dense shoals of bream using the structures as shelter, while a marbled ray skated across the sandy bed below. Two sunken fishing boats, deliberately placed to supplement the habitat, have become hotspots for predator species.

“It is about acceleration,” explained one of the marine biologists guiding the citizen scientists through the site. “We are giving nature a head start. In rocky seabeds, complex structures create niches. More niches mean more species. It sounds simple, but getting the materials and the placement right is everything.”

That is the crucial data point PHAROS is collecting. The Parque de la Atlántida proves that if you build it, they will come. But the question the scientists are now asking is: can we build it better? And can we do it on a scale large enough to mitigate the damage done by trawling, pollution, and rising sea temperatures?

For the citizens who descended into the depths that day, the experience was a powerful piece of advocacy. To see a barren sandflat transformed into a thriving reef in less than a decade is to witness hope in an era usually dominated by marine despair.

As the Golden Shark submarine slowly ascended back towards the glare of the Canarian sun, leaving the “sunken city” to the barracuda, the implication was clear. The myths that once spoke of lost worlds beneath the waves may need updating. Here, at least, the world beneath the waves is not lost, it is being rebuilt, one pH-neutral block at a time. The challenge for PHAROS now is to prove this can work in the cold, dark waters of the Arctic just as effectively as it does in the luminous Atlantic off Gran Canaria.

- Posted In:

- PHAROS News