The Promising Outlook for Irelands’ Bantry Bay Seaweed

The Promising Outlook for Irelands’ Bantry Bay Seaweed https://pharosproject.eu/wp-content/uploads/2026/02/mathieu-habegger-aSPgmeUQSrc-unsplash-2-1024x683.webp 1024 683 PHAROS Project PHAROS Project https://pharosproject.eu/wp-content/uploads/2026/02/mathieu-habegger-aSPgmeUQSrc-unsplash-2-1024x683.webpOn the wave-battered coast of West Cork, a demo experiment in balancing aquaculture with ecology is entering a critical phase. The PHAROS Ireland Demonstration, led by Julie Maguire, Research Director of the Bantry Marine Research Station (BMRS), is testing a compelling hypothesis: can strategically farmed macroalgae, co-located with a commercial salmon farm, mitigate environmental impact while enhancing biodiversity? The results from the first full growth season (2024-2025) are now in, and they paint a picture far more intricate and unexpected than simple cause and effect.

A Season of Growth and Unexpected Turns

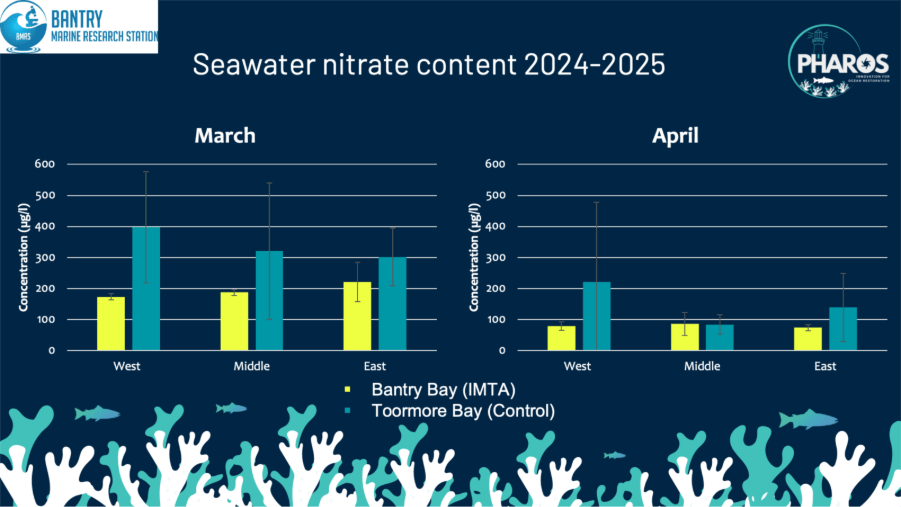

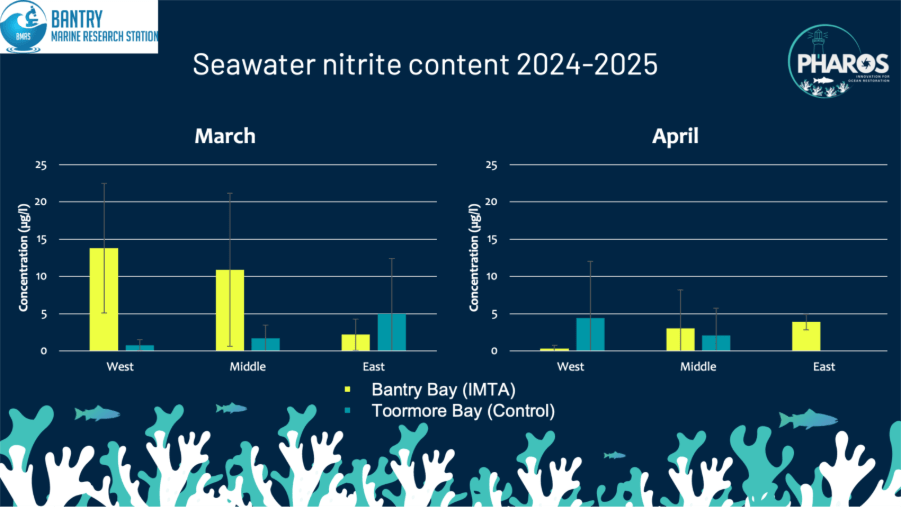

The demonstration’s design is elegantly comparative. In Bantry Bay, kelp lines are deployed alongside a Mowi salmon farm, constituting the Integrated Multi-Trophic Aquaculture (IMTA) site. A control site, in nearby Toormore Bay, hosts seaweed without the influence of fish farming. The goal is to measure differences in growth, nutrient uptake, and ecological development.

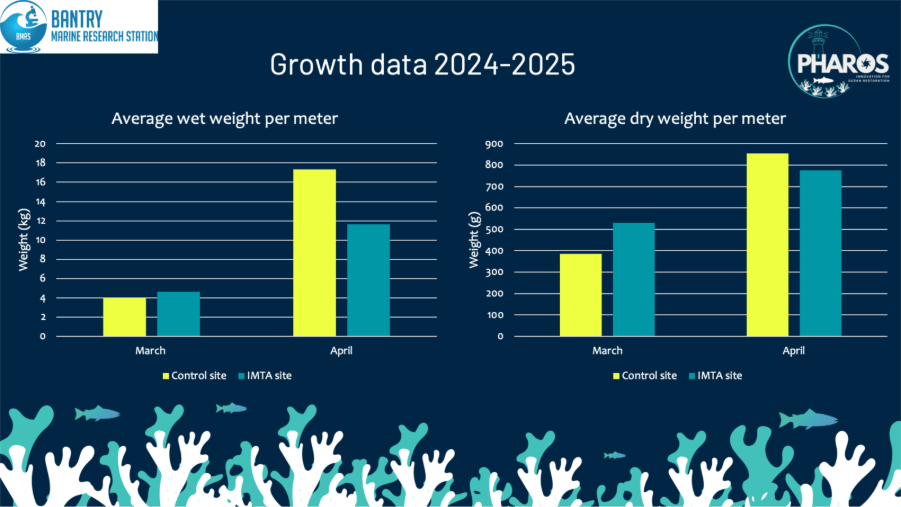

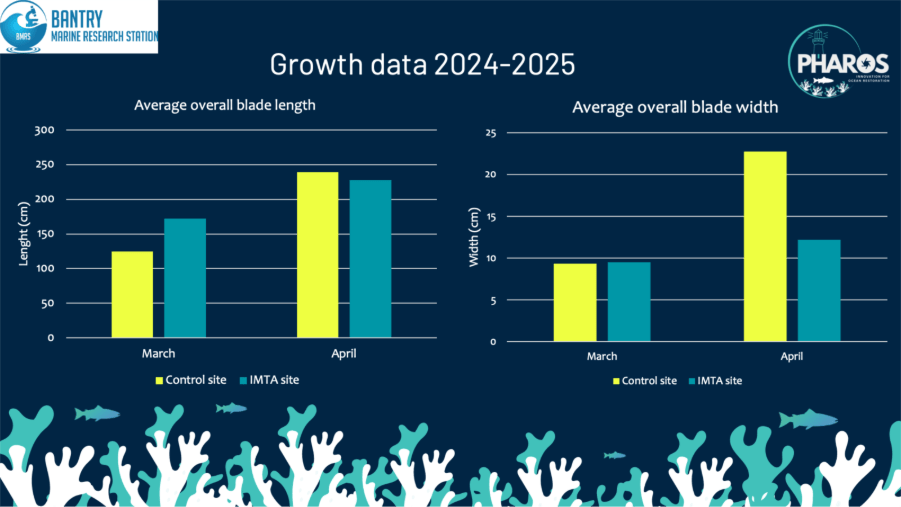

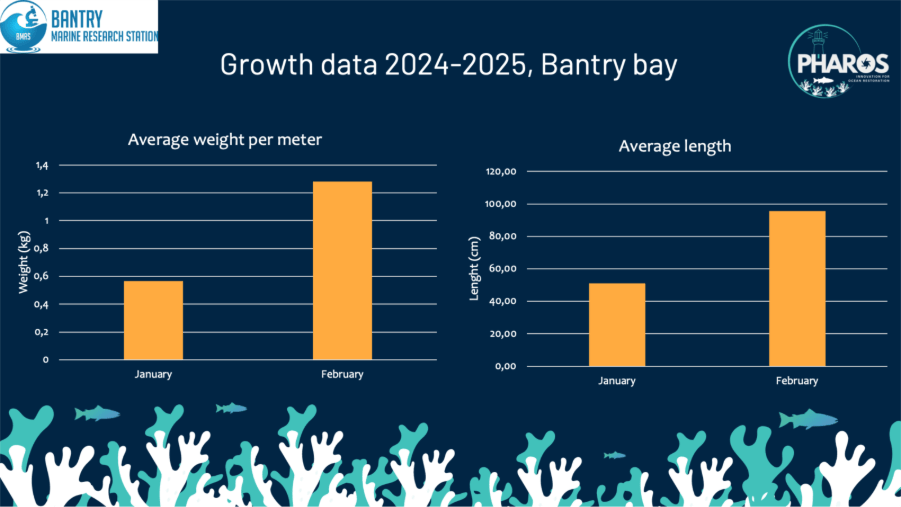

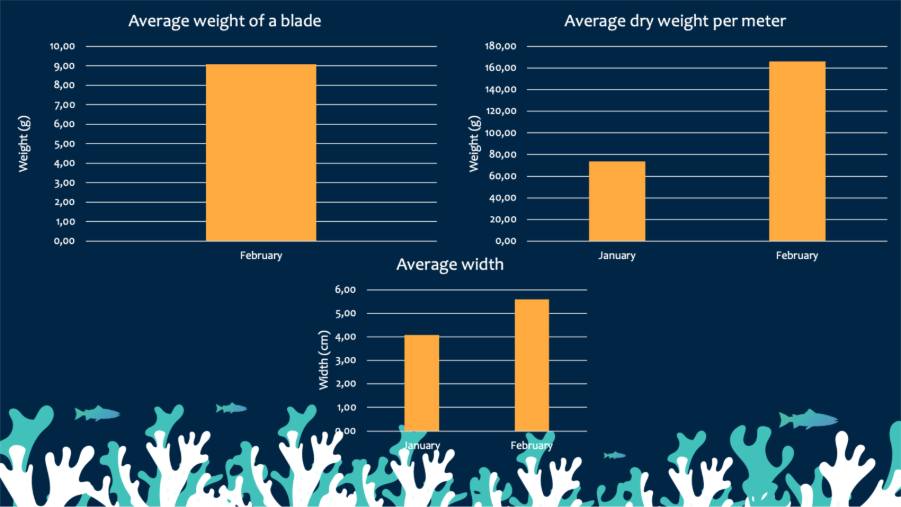

Throughout the 2024-2025 season, monthly monitoring tracked seaweed growth and seawater composition. The initial data held a surprise. While the IMTA site showed stronger growth earlier in the season, the final harvest in April revealed a striking reversal. The control site in Toormore Bay “outperformed the IMTA site,” yielding a remarkable 17 kilograms per metre compared to nearly 12 kilograms at the IMTA site. This was unexpected; the prevailing assumption was that proximity to the salmon farm’s nutrient plume would fuel superior growth.

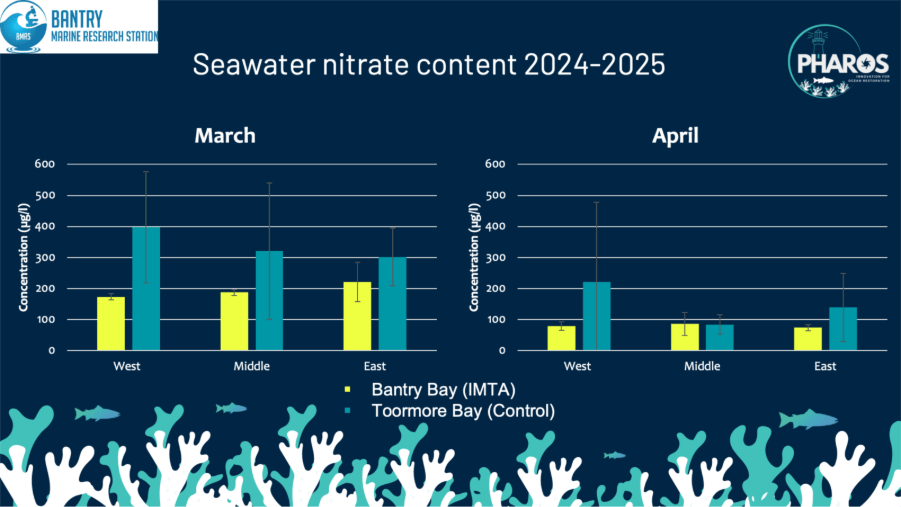

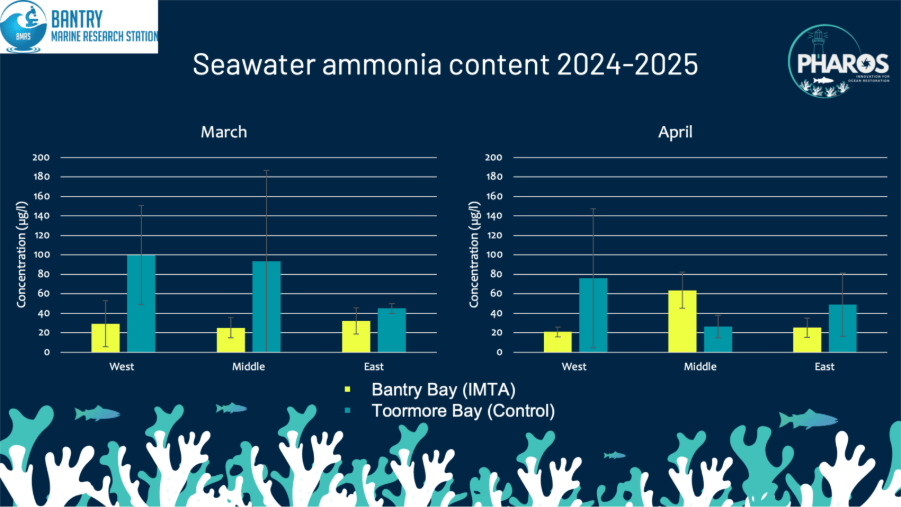

The explanation appears to lie in the water chemistry. Analysis of seawater nutrients showed that, contrary to expectations, the control site generally exhibited higher concentrations of ammonia and nitrite throughout much of the sampling period. “This can be explained by the fact that there were more nutrients at the control site compared to the IMTA site,” Maguire notes. The source of these elevated nutrients in Toormore Bay remains an open question, underscoring the complex, localised nature of coastal nutrient dynamics.

A significant caveat to the seasonal story is the lack of control site data for January and February, due to severe weather conditions that prevented safe sampling. This gap highlights the logistical challenges of consistent marine fieldwork and means the full growth trajectory at the control site is partially obscured.

A Deeper Dive into a Hidden Community

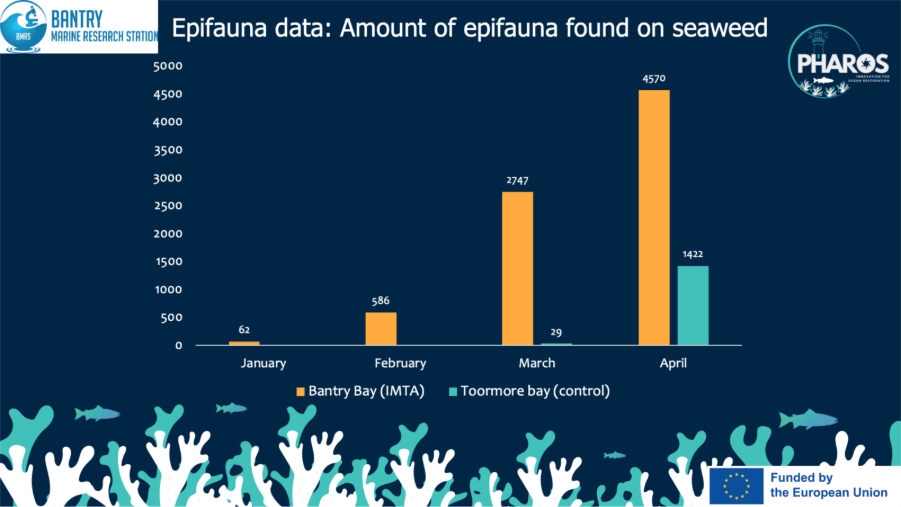

Beyond mere biomass, the study meticulously analysed the epifauna, the community of tiny invertebrates living on the seaweed blades. Here, the influence of the salmon farm became profoundly clear, not in the seaweed’s weight, but in the life it supported.

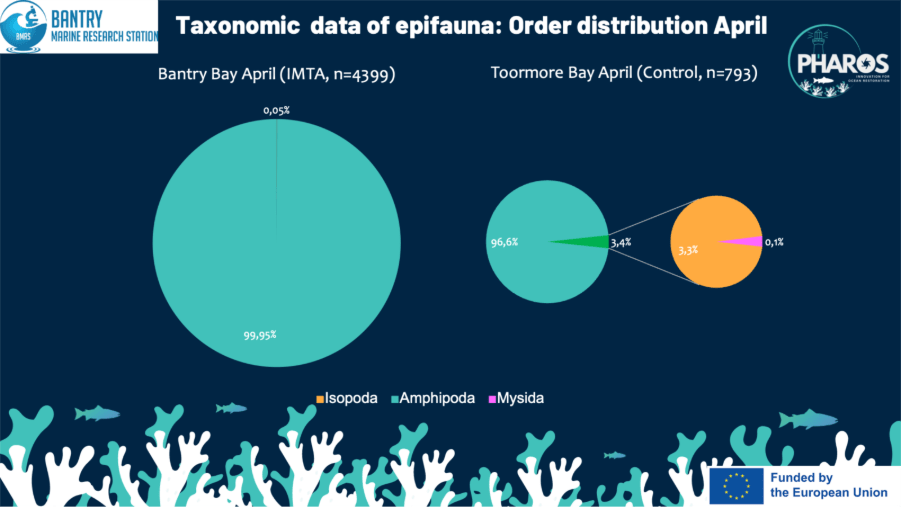

The abundance of individuals was drastically higher at the IMTA site. In April alone, researchers counted 4,570 individuals on samples from Bantry Bay, compared to 1,422 at the control site. This disparity, Maguire suggests, is “probably caused by the presence of salmon which excrete readily available nutrients,” and may also be influenced by differences in current speed and other hydrological factors altered by the farm structures.

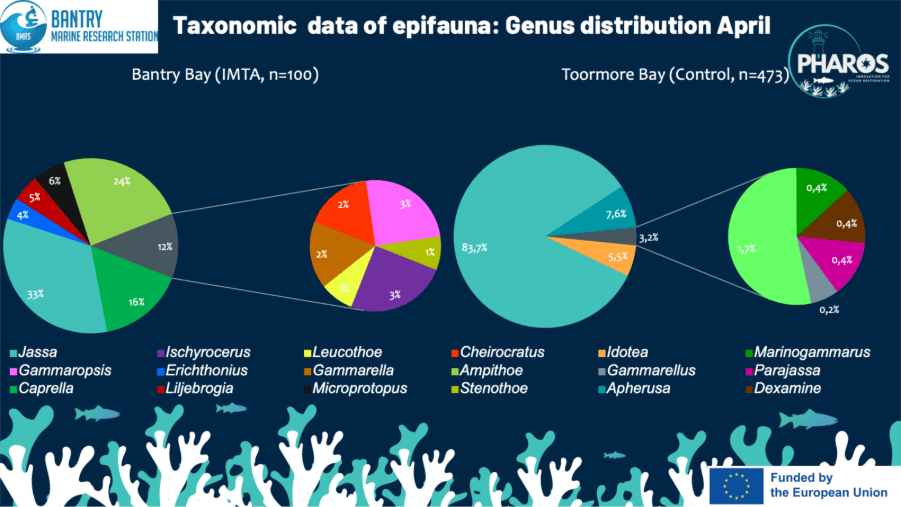

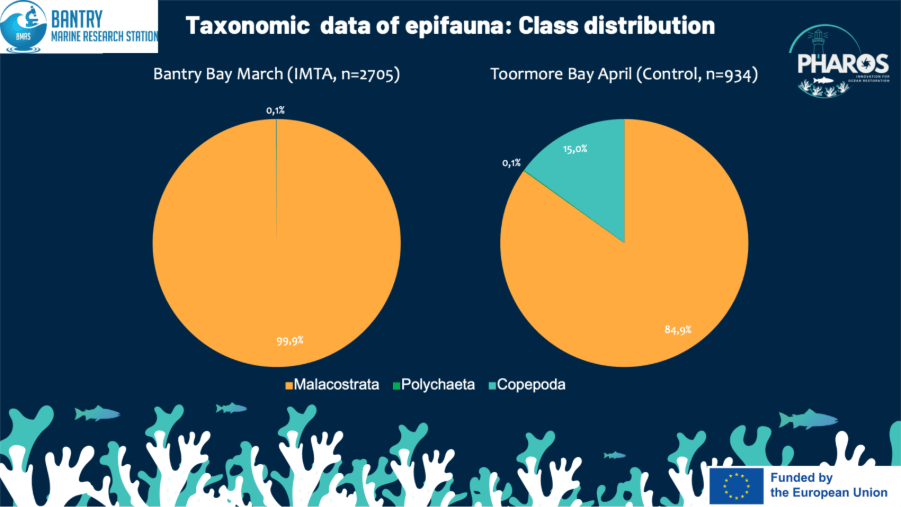

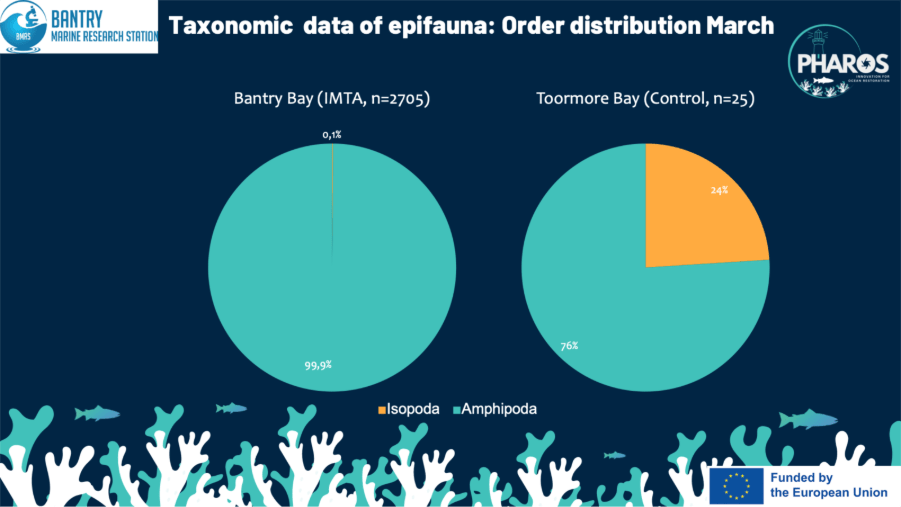

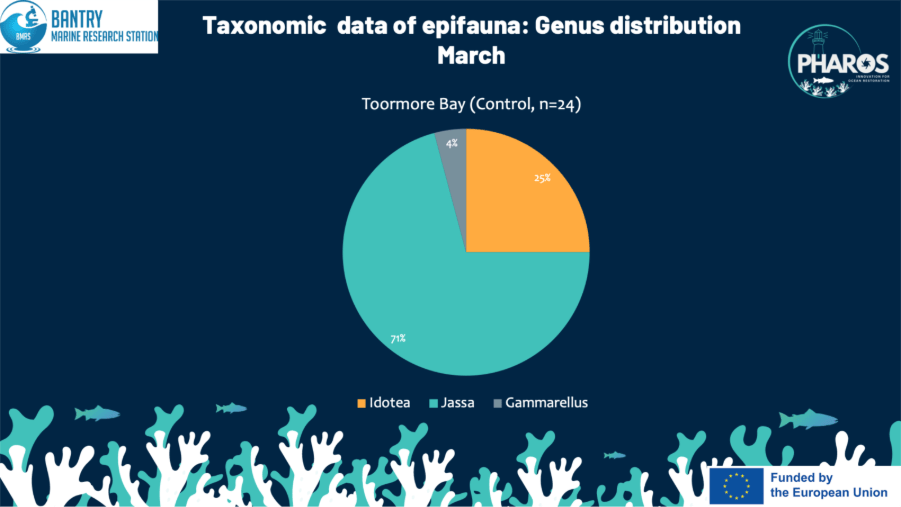

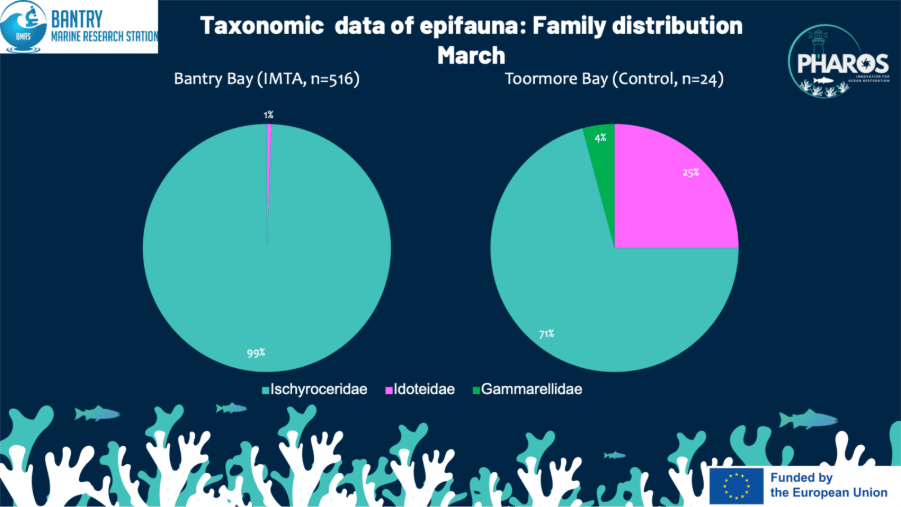

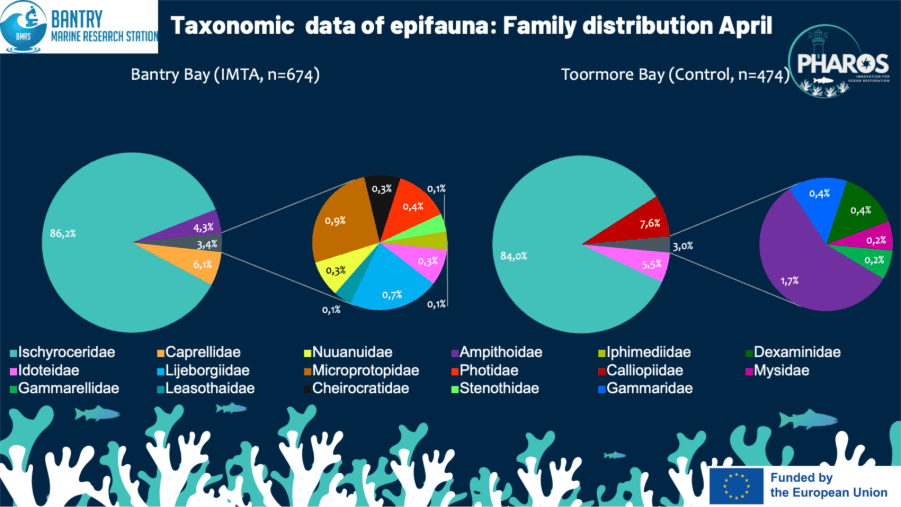

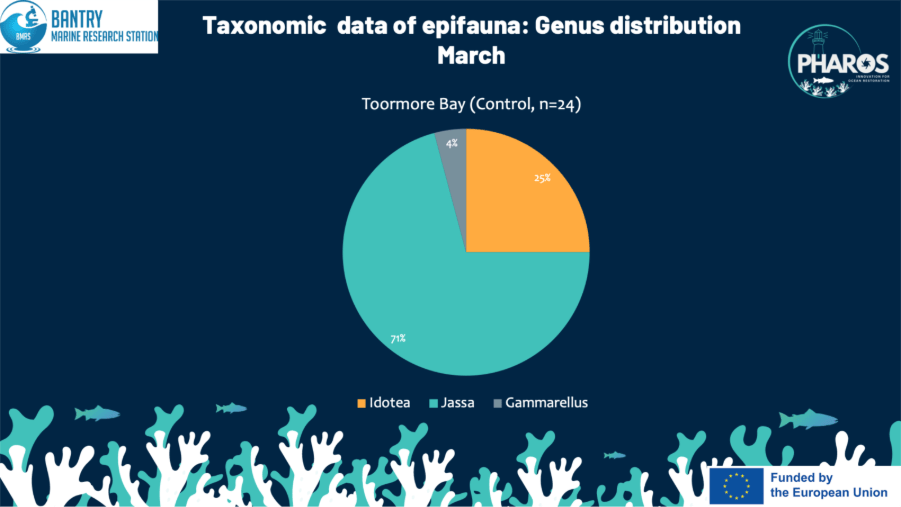

However, this abundance tells only half the story. Biodiversity, measured as the variety of species present, followed an inverse pattern. The control site, with fewer overall organisms, hosted a greater diversity of epifauna. Taxonomic breakdowns reveal a fascinating hierarchical picture. At the class level, the community was dominated by Malacostraca (crustaceans like amphipods and isopods), with smaller representations of Polychaeta (bristle worms) and Copepoda. The order and family-level data show a progression from a simple community in winter (where all epifauna in January and February belonged to a single order) to a significantly more complex one by April, encompassing multiple families such as Ischyroceridae, Caprellidae, and Gammarellidae.

The most startling finding lies at the genus level. A total of 18 distinct genera were identified across both sites. Yet, the overlap between the two bays was minimal. The IMTA site hosted 12 genera, dominated by Jassa (33%), Ampithoe (24%), and Caprella (16%). The control site featured 8 genera, with Jassa overwhelmingly dominant at 83.7%, revealing that the two adjacent bays are fostering almost entirely distinct ecological communities on the seaweed itself.

Synthesis and Forward Trajectory

These results present a nuanced initial report card for the IMTA concept. The seaweed growth benefit was not straightforward, being outperformed by the control under the specific nutrient conditions of the season. However, the salmon farm’s role as an ecosystem engineer is undeniable, fundamentally reshaping the associated epifaunal community towards higher abundance but lower diversity, and favouring a different suite of species.

For the upcoming second reporting period, the BMRS team plans to continue the rigorous seasonal sampling for 2025-2026, complete the remaining analysis from the first season, and determine the optimal statistical frameworks for this complex dataset. A core principle of the project is open science; all raw data will be deposited in a repository, and a publication plan is being developed to share these detailed findings widely.

The Critical Context of a Fallow Year

This ongoing work will soon be overlaid with a vital natural experiment. As confirmed in earlier discussions, the Mowi salmon farm will enter a fallow period in 2026. This pause in operations is a rare opportunity. It will provide a pristine baseline of “control conditions” within Bantry Bay itself, allowing scientists to disentangle the farm’s specific influence from the bay’s natural background state. Historical stable isotope analysis from a previous fallow period showed that 93% of the nitrogen in the seaweed was derived from the salmon, a powerful testament to the integration within the IMTA system. The upcoming fallow year will enable a before-and-after comparison of unparalleled clarity when the farm resumes.

The Ireland Demo continues to evolve as a living laboratory. It is demonstrating that the path to sustainable marine multi-use is not a simple equation of adding seaweed to absorb waste. Instead, it is a delicate navigation of interconnected variables: unpredictable nutrient flows, starkly different ecological succession patterns, and the ever-present challenge of logging data in a forbidding marine environment. Each finding, whether expected or surprising, adds a critical thread to the understanding of how we might better integrate food production and ecosystem restoration in our coastal seas.

- Posted In:

- BLOG